Nestled in the foothills of East River Mountain, placed appropriately along narrow winding roads wrapping in and around Virginia’s rocky creek banks, are small communities where our people have lived. Falls Mills, Clearfork, Pocahontas, Rocky Gap and Mudfork are all in the county of Tazewell. The people living on the hillsides and in the hollows between the mountains have been there most of their lives. Even for hundreds of years, the traditions of backwoods life have remained the same. Countercultures gradually influenced the attitudes and practices of the young, but many continue to live simply, just as their parents and grandparents before them. Generations have lived, raised their families and are laid to rest among their deeply planted roots – beneath the show of the mountains in a region known as Appalachia.

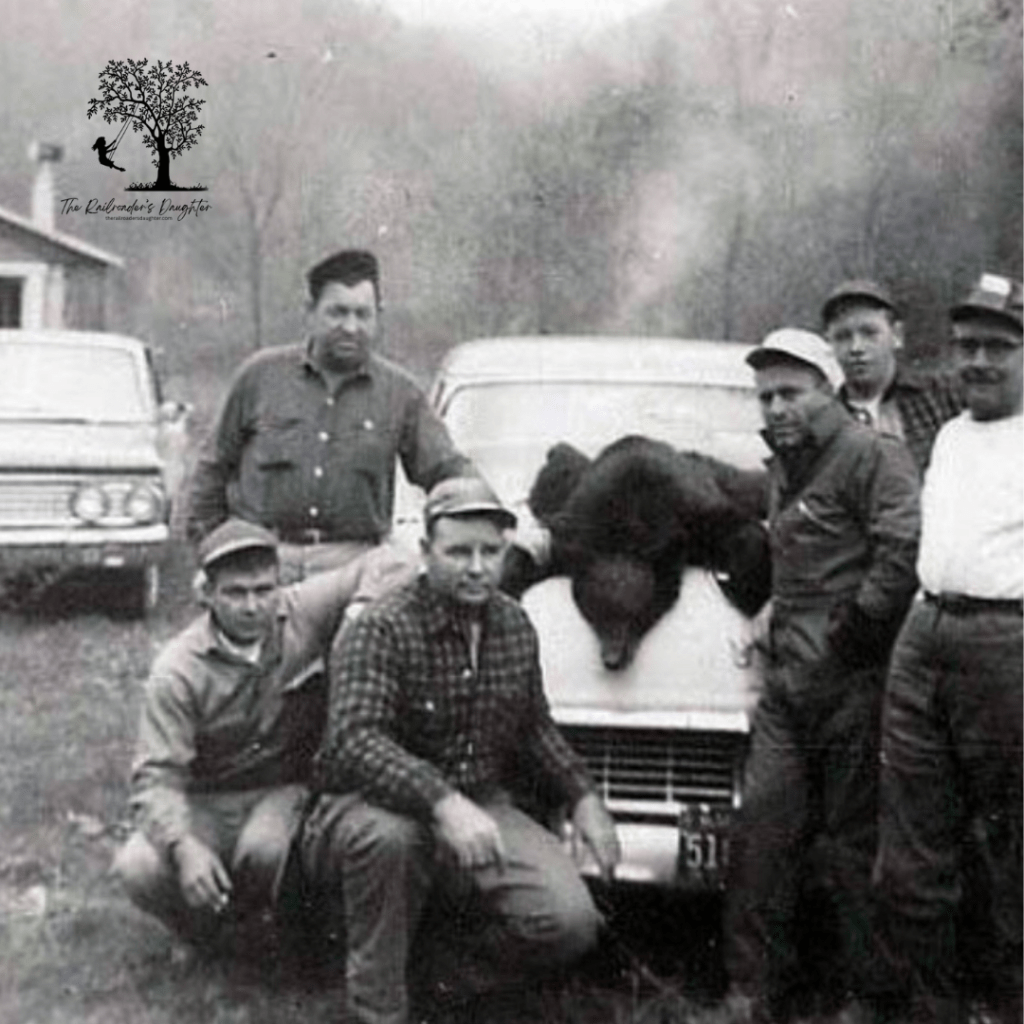

Men in Appalachia are known by biblical names like Jacob, Samuel or Daniel. When harvest time is over, they cloak themselves in long johns, flannel shirts and heavy winter coats and hats, then disappear into the woods. Hunting deer and bear and sometimes rabbit or squirrel seems to be their passion, and also a source for providing food for the family.

After hunting season, these rugged men go back to working serious jobs like coal mining or railroading. In spite of good wages, those who are brave enough to travel deep into the earth digging out coal deposits look forward to the day they can move on to hauling coal for the railroad company. Huge iron steam engines spewing out clouds of white smoke surrendered themselves to streamline diesel locomotives. In the coal fields dust settles on houses and cars like a veil of soot, clinging to surfaces and obscuring them. Everyone knows that coal mines reluctantly give of themselves – often collapsing on those within, taking fathers and brothers to an early grave. Some workers escape being crushed in a coal shaft only to eventually fall victim to the agonizing death of black lung disease.

On Sundays, the families living along these ridges and within the valleys put on their best clothes. It may be a hand-me-down suit that belonged to Uncle Charlie Davidson or that special print dress with a ruffle that grandmother made. And after church, they all go to relatives houses and eat a home cooked dinner with all the fixings and talk about nothing. They sit around the kitchen table or on the front porch glider and eat dessert and drink coffee. The children play in the yard and climb the weeping willow tree until evening when it’s time to go back to church. These mountain people are serious about God’s example to rest on Sunday. God created them and their mountains; they believe it.

Not so different from the men, women in the mountains of southwest Virginia are also accustomed to hard work. It seems to be their calling in life to raise children and keep the house. The kitchens where Sarah, Mary Jane or Bertha live always smell good from cooking and canning. To avoid being wasteful, the homemaker puts leftovers on a plate over the warm stove. Cold cornbread will likely be eaten later, crumbled in buttermilk. When winter’s weather blankets the summer, Appalachian women gather by the fireplace in the living room to quilt. They embroider family names and special dates on their patchwork quilts. They look at family photographs of expressionless faces hanging on the wall and record births, marriages and deaths in the family Bible. God and family are most important.

In the fall of the year, children climb the colorful mountains painted with autumn leaves, and they run through the woods. They get stained hands from scooping up black walnuts covered in a thick outer husks and prickly fingers from plucking chestnut-like chinquapins from spiny burrs. Winter’s snow encourages the children to ride their sleds for hours on end. There’s no need for costly toys in Appalachia because they love the outdoors and have no expectation of more. They feel safe playing within the protective natural boundary of the mountains, isolated from a world they’ve never seen.

When someone dies, Appalachian people gather at a wake where they view the body and pay their respects. The women cook and take food to feed and comfort, and to show compassion to the grieving family. The men sit alongside each other with tears in their eyes, and they share stories they fondly remember. The funeral procession from the chapel to the cemetery is long and stately and somewhat presidential. Cars line up behind the hearse, following ceremoniously down winding roads to the cemetery. People gather round and the men reverently remove their hats. The minister speaks again, and everyone stays at the graveyard until the body is respectfully at rest in the family plot.

Webster defines Appalachia as the highland region of the eastern United States extending from northern Pennsylvania through northern Alabama, characterized generally by poverty. Literally, this is true. Appalachia is an area of mountains and hollows scattered with dirty, rut roads leading to worn-out wooden shacks and privies. The people work long hours and hard jobs and have little hope for relief. Nevertheless, Appalachia is much more than a region of impoverished mountain people. Appalachia is home to an honorable way of life filled with a wealth of good values, contentment, and appreciation for life. Appalachia is home to God-fearing people who know who they are and what life means – accepting the blessings of a rich heritage and salvation from the Savior.

_______________________________________________________

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; He shall bruise your head and you shall bruise His heel.” Genesis 3:15

From the moment that Adam and Eve rebelled against God, the greatest need the world has had is a Savior. That Savior was promised in the above scripture and Jesus Christ is the fulfillment of that prophecy.